by Susie Aft, Autum Martin, Anna Anna, Candice Talkington and Tracey Dorff

Background

The Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) is a Medicare provider designation created by Congress to address the growing concern over loss of access to rural health care services due to hospital closures. The primary goals of the REH designation are to maintain critical healthcare access for rural communities and reduce the risk of hospital closures. To implement this designation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) established regulatory guidance for REHs.[i] As of January 2023, Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) and small rural hospitals with no more than 50 beds that were open as of December 27, 2020, may opt to convert to the REH designation in accordance with the conditions of participation (COPs) outlined in the CY 2023 Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment System Final Rule. REH is the first Medicare provider type added since Congress created the CAH designation through the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

Congress allocated funding to the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), a division of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), to support hospitals exploring or converting to the REH designation through dedicated technical assistance (TA)[ii]. The Rural Health Redesign Center (RHRC) was awarded a Cooperative Agreement with FORHP to serve as the national REH Technical Assistance Center (TAC)[iii].

Through the REH TAC, hospitals have access to a comprehensive suite of services, including REH program education, financial modeling, application assistance, stakeholder and community engagement resources, strategic planning, and regulatory compliance support. The TAC customizes its assistance to meet the specific needs of each hospital and its community, while also sharing best practices among hospitals facing similar challenges.

The REH TAC grant funds all TA services, allowing participating hospitals to focus on optimizing operations and exploring new service lines that support long-term financial sustainability. In addition to TA, FORHP also funds the tracking of state REH policies and licensure by the National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL)[iv] and the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP)[v], and supports coordination and information-sharing with State Offices of Rural Health (SORHs). These efforts help ensure that hospitals and stakeholders have access to up-to-date policy information and state-level guidance.

In 2024, the REH TAC launched the REH Peer Network—a collaborative, peer-to-peer learning community that offers ongoing TA and shared learning opportunities for REHs that choose to participate. As of January 2025, the TAC has engaged with 164 hospitals to provide education on the REH designation; of these, 107 have undertaken feasibility assessments, and 33 hospitals that had converted to REH status[vi] are receiving ongoing, post-conversion support.

Introduction

A key priority of the REH TAC is to support hospitals that have converted to the REH designation—or are considering conversion—in making informed, data-driven decisions about expanding service lines to better meet the needs of their communities. To aid this effort, the RHRC developed the Health Services and Needs Assessment (HSNA) tool, which analyzes geographic and demographic data in relation to existing hospital services within rural communities using various public data sources[vii],[viii] in conjunction with a subscription claims-based platform[ix].

The REH TAC provides the HSNA to all REHs as well as to hospitals exploring the REH designation. This tool helps organizations evaluate which service lines are most likely to address community needs and improve access to care. Due to differences in timing, some hospitals receive their HSNA before completing the REH conversion process, while others receive it afterward. The HSNA assesses several key factors, including:

- Community attributes

- National quality performance (if applicable)

- Regulatory activity and accreditation status (if applicable)

- Social Drivers of Health (SDoH) within the county of their establishment

- SDoH stratifications (when available)

- Current facility services available

- Geographic analysis of surrounding facilities, including services offered

- Geographic distance of Level I and II Trauma centers

- Emergency Medical Services (EMS)/ambulance resources

- Healthcare Professional (HCP) Shortages including Medically Underserved Area/Population (MUA/P) scores and Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) scores

- Implications for services stratified by community outreach, behavioral health, primary care/Rural Health Clinic, hospital services

- Recommendations for improving quality metrics

- Facility health services strategies

- Community outreach opportunities

- Special considerations (e.g., marketing, Patient Family & Advisory Councils)

This HSNA data has proven impactful to REHs and other hospital designation types, assisting organizations to explore realistic services to consider implementing to improve care in their rural community. The assessment was designed to be integrated into their strategic planning and community service initiatives. In addition to evaluating county required metrics, Medicare claims-based data and related health needs, each HSNA provides recommendations to develop a health services program that aligns with the CMS reporting metrics incorporated into National Quality Reporting (NQR) Program(s).

Findings & Key Learnings

All hospitals that engage with the REH TAC receive a HSNA to support strategic decision-making. As of September 2024, 36 HSNAs have been completed. The REH TAC conducted individual review sessions with more than half of these hospitals to facilitate discussions around facility-specific challenges, technical assistance needs, and opportunities for peer learning or collaboration with other REHs. The remaining HSNAs have either been scheduled for review or shared directly with the hospitals for independent evaluation. A few organizations elected to forgo the virtual review process with RHRC.

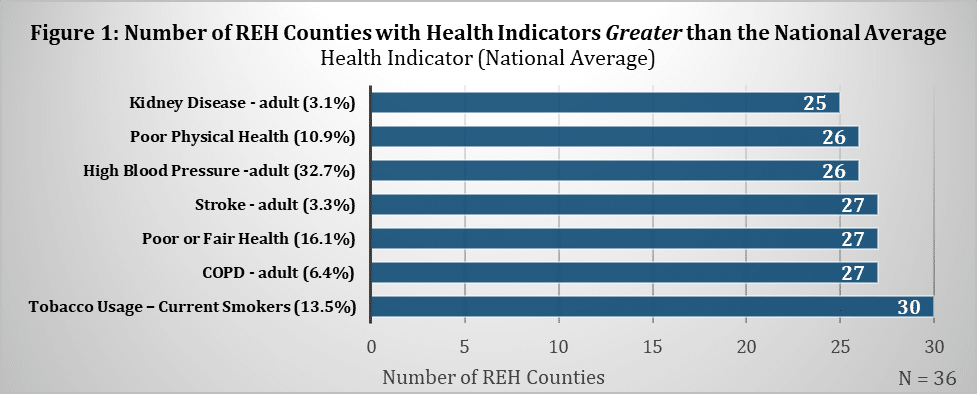

The REH TAC aggregated health data indicators to assess trends across REH communities. This analysis revealed consistent patterns of poorer health outcomes in rural areas compared to national averages (Figure 1), underscoring the increased vulnerability of the populations served by REHs. For example, tobacco use in 30 counties showed above-average prevalence compared to the national standard of 13.5% of the population smoking. Similar trends were observed across several chronic conditions, including higher rates of stroke prevalence above the national average of 3.3% of the population ever having a stroke. These findings highlight the critical need for targeted service line development and community health interventions in REH-designated areas.

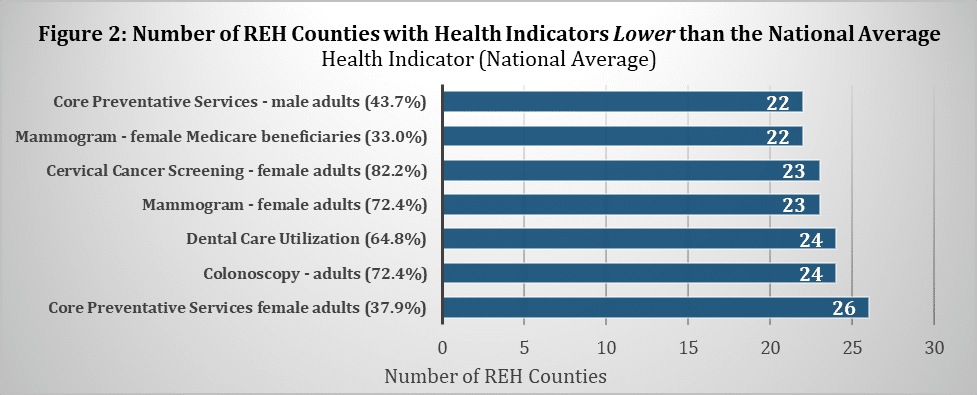

The TAC analyzed the availability of preventive services across REH communities and found that 22 of the 36 REHs provided fewer preventive services than the national average (Figure 2). Notably, women’s preventive services ranked below national benchmarks in 26 of these communities, highlighting a significant gap in access to essential care in rural areas.

Building on the quantitative data collected through the HSNA process, the REH TAC leveraged its ongoing engagement with participants in the REH Peer Network to facilitate discussions around operational challenges and service line expansion. These peer-to-peer conversations helped surface common issues faced by rural hospitals, including:

- Extreme financial strain affects the ability to implement or expand services. Some REH leaders noted that the REH monthly facility payments helped to stabilize operations while other administrators reported the facility payments helped them breakeven but are not significant enough to support service line expansion.

- Optimization of wellness exams and preventative services within primary care settings. Many rural communities lack adequate cancer screenings, core preventative services, and low vaccination rates. Most REH facilities provide some of the preventative services, such as vaccine clinics and smoking cessation programs. Cancer screenings performed at the REH may be cost-prohibitive based on smaller populations, staffing, recruitment of physicians and the cost of procedural and diagnostic equipment. REH primary clinics often lack processes and standard work to streamline and optimize wellness exams.

- Need for increased access to mammography and endoscopy services. REHs have identified that costs associated with provider recruitment, staffing, and lack of equipment can hinder their ability to expand services lines to meet community needs. Some REHs have implemented mobile diagnostic services with intermittent and sporadic availability. Other REHs struggle to compete with other facilities that have updated 3D mammography, ultrasound, and MRI services.

- Need for outpatient behavioral health services. REHs, like other rural hospitals, face challenges with recruiting behavioral health providers to rural areas. Some REHs have implemented telehealth as an option for behavioral health services; however, equipment for telehealth, reimbursement, and patient preferences may impact the effectiveness of providing this service virtually.

- Need for cardiac stress testing and cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation. There is a significant benefit of offering cardiopulmonary services to rural areas that have a high prevalence of related chronic disease, particularly in geographically isolated areas. However, the financial stress of rural hospitals has hindered their ability to implement cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation care. Many of the REH communities lack these services requiring patients and their support networks to travel farther to other facilities, causing significant hardships.

- Transportation challenges. REHs identified significant challenges related to both emergency and non-emergency transportation. Many communities rely on volunteer-based ambulance services, which face staffing shortages and financial strain due to the high costs of equipment and supplies. Additionally, limited access to non-emergency transportation often creates barriers for patients needing care at neighboring facilities.

- Issues with the acceptance of REH patients to critical access hospitals and acute care hospitals. Several factors have impacted the transfer of patients to other hospitals such as, (1) availability of EMS services for transportation, (2) lack of understanding by other hospitals of services provided by REHs, and (3) confusion about level of care.

- Challenges with recruitment and retention of physicians and allied health practitioners in rural areas. Healthcare workforce shortages are a nationwide concern, but the impact is especially acute in rural areas. Few REHs operate Graduate Medical Education (GME) programs, limiting the pipeline of new physicians. Existing medical staff are often long tenured, with limited options for replacement as they approach retirement. Many REHs have small, organized medical staff and rely heavily on allied health professionals (AHPs) to meet patient care needs. AHPs have proven to be essential in delivering consistent, high-quality care in these resource-constrained environments.

Conclusion

Rural communities consistently experience higher rates of chronic conditions and poorer health outcomes, a situation further compounded by limited healthcare options, a lack of specialized services, and the financial strain faced by hospitals and clinics. The HSNA has provided an objective framework to confirm that REH communities reflect these same challenges. Conversion to REH status has played a critical role in preserving access to care for vulnerable populations in these areas.

REH communities also exhibit higher rates of adverse SDoH compared to national averages, directly impacting overall community health. These findings underscore the pressing need to expand primary care, preventive health screenings, outpatient behavioral health services, chronic disease management, and core hospital services within REH-designated regions.

Following REH conversion, the REH TAC has observed a shift among REH facilities from crisis management toward strategic service expansion. Feedback from REH administrators on the Health Services and Needs Assessment (HSNA) has been overwhelmingly positive. Administrators found the recommendations for service expansion and community outreach to be realistic, achievable, and aligned with local health needs. Each hospital received tailored recommendations, but common themes emerged—primarily addressing gaps in care linked to community health challenges shown in the HSNA data. Examples include implementing chronic care management and preventive services through patient navigator programs or organizing county-specific influenza vaccination clinics targeting vulnerable populations.

REHs use the data analysis and best practice strategies from the HSNA to create individualized action plans that improve health services and expand access to care in their communities. The REH TAC continues to support hospitals throughout this process by providing TA in specific areas such as service line assessment, financial modeling, regulatory compliance, strategic planning, clinical best practices, grant research and education, and leadership development. In addition to this targeted support and in-depth educational sessions, participation in the REH Peer Network offers REH leaders a valuable forum to exchange best practices, share operational challenges, and collaborate on innovative solutions to enhance performance and community impact.

Get Connected

If you are interested in receiving updates and key findings from the TAC, subscribe to our newsletter or visit the RHRC website. To receive support from the TAC, contact us at REHSupport@rhrco.org.

Disclaimer

The Rural Health Redesign Center (RHRC) provides technical assistance to organizations on behalf of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). While RHRC strives to offer accurate and up-to-date guidance, the information provided in this resource is for general informational purposes and should not be considered legal, regulatory, or financial advice. Hospitals and healthcare providers are responsible for ensuring compliance with all applicable federal, state, and local regulations, including those set forth by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), state health departments, and other governing bodies. RHRC does not assume responsibility for an organization’s compliance status or guarantee regulatory approval and healthcare facilities are encouraged to consult with legal, regulatory, and financial professionals for advice.

As a technical assistance provider to rural stakeholders, the Rural Health Redesign Center provides access to a wide range of resources on relevant topics. Inclusion on the Rural Health Redesign Center’s webpage or presentations does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by the Rural Health Redesign Center or the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Resources

[i] CMS. (2023). Rural Emergency Hospitals. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/health-safety-standards/guidance-for-laws-regulations/hospitals/rural-emergency-hospitals

[ii] Section 711 of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 912); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 (P.L. 117-103), Division H, Title II

[iii] Rural Health Redesign Center (2023). 2023 Annual Report, Expanding Beyond State Lines. Courtesy RHRC, retrieved April 29, 2024. https://rhrco.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2023-RHRC-Annual-Report_FINAL-v.2.pdf

[iv] NCSL. (2024). Rural Emergency Hospitals. https://www.ncsl.org/health/rural-emergency-hospitals#toc2

[v] NASHP. (2023). Rural Emergency Hospitals: Legislative and Regulatory Considerations for States. https://nashp.org/rural-emergency-hospitals-legislative-and-regulatory-considerations-for-states

[vi] University North Carolina Chapel Hill Cecil G. Sheps Center f or Health Services Research. Rural Hospital Closures. Courtesy UNC, retrieved April 25, 2024 https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/

[vii] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (2016-20). Data Profiles. Courtesy of US Census Bureau, retrieved April 29, 2024, https://data.census.gov/profile?q=United%20States&g=010XX00US

[viii] University of Wisconsin, County Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023 County Health Rankings National Findings Report. Courtesy Univ. Wisconsin, retrieved April 26, 2024

[ix] University of Missouri. SparkMap. Report retrieved October 2023 – September 2024. Accessed https://sparkmap.org/